Steel Warriors Guarding the Border: Training Fighters to Liberate the Occupied Territories

It is noisy in the clearing. “Man down! Medic!” “How you doing, buddy? Can you hear me?” “Cover!” “Contact on the left!”

The grenades that explode are drill grenades. The moans of the ‘man down’ are somewhat theatrical and mixed with witty remarks like, “Be quiet—you’re unconscious! Or maybe not, you’d better be conscious!” But all the algorithms are presented as clearly and realistically as possible. Donbas Frontliner visited the exercises of the 15th Mobile Border Guard Unit, The Steel Border, one of the units of the Offensive Guard, to talk to the fighters.

Nine new brigades of the National Guard, the National Police, and the State Border Guard Service are formed to fulfill a specific mission: the liberation of the occupied territories. Offensive operations are quite different from defensive operations, so the fighters are trained accordingly. The Offensive Guard has another telling feature: people join it only of their own free will.

“We followed our commander, a defender of Azovstal”

“The Steel Border is a unit made up of volunteer fighters,” says Lieutenant Colonel Ivan Shevtsov, deputy head of the 15th Mobile Border Guard Unit. “Experience from combat operations has shown that volunteer battalions achieve much better results, so we ran a recruitment campaign and recruited only volunteer fighters. Both civilians and soldiers who have already served in other units of the State Border Guard Service. The backbone of the unit are the fighters with combat experience. They are defenders of Azovstal and soldiers who were on active duty in Kherson and Bakhmut. These people know what they have to do and what to expect.”

When the unit was just formed, the ratio of experienced fighters to rookies was 50/50, while now it is about 80/20 in favor of the experienced fighters.

Shevtsov has been serving in the State Border Guard Service for 24 years. On February 24, 2022, he was in Kherson. He remembers that just a couple of days earlier, on February 22, he was on the Arabat Spit with the BBC journalists filming a report there.

He says, “First of all, everyone here followed the commander. The commander of the Steel Border is Colonel Valeriy Padytel, a Hero of Ukraine and defender of Azovstal. He was held in captivity for six months. When I learned that he would take command of the Steel Border, I joined this unit without hesitation because I had served with him and knew what kind of person he was. And from what I have heard from other soldiers, many of them joined that unit because of the commander.”

Like the other brigades of the Offensive Guard, this unit was created on the Ministry of Internal Affairs initiative. Shevtsov admits that it is not a typical formation for the State Border Guard Service:

“Usually, we have only linear border guard units and a mobile border guard unit, Dozor. But this is a whole brigade, large and with all kinds of weapons. We have our own artillery, aerial reconnaissance, and portable air defense systems. So this is a powerful combat unit that is now being trained for combat operations to clear Ukrainian territory.”

It’s not just about the new missions the fighters are being trained for but also about new approaches that meet the standards of NATO. According to Shevtsov, until recently, Soviet-era approaches prevailed in Ukraine, when the mission had to be accomplished at any cost.

“Now we are moving toward a completely different mindset, a different vision,” he says, “and the most important thing for us is that our soldiers stay alive and healthy. Our unit is fully staffed. Our warriors have been trained in different areas, and today we are ready to conduct missions.”

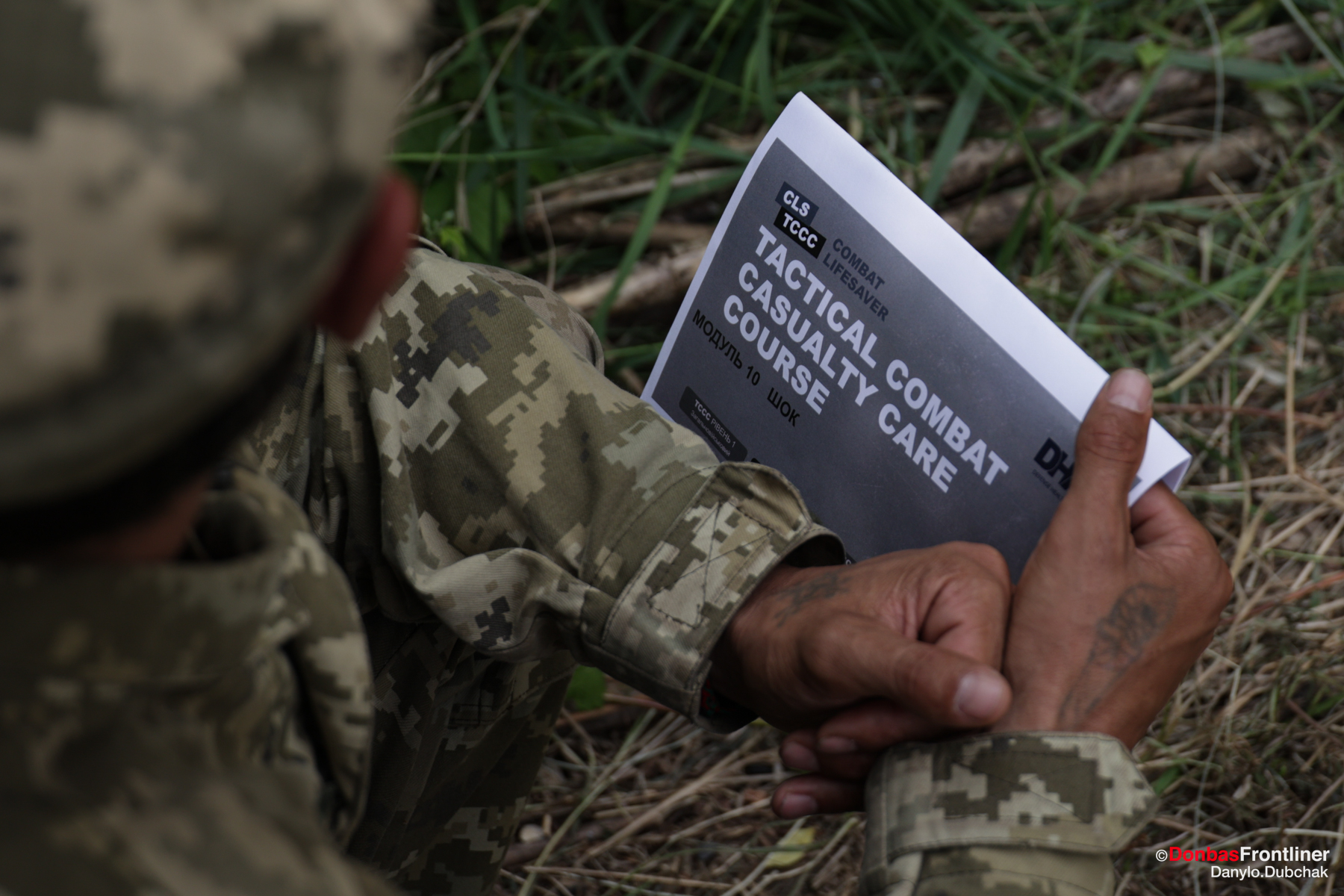

The Steel Guard fighters are trained by foreign and Ukrainian instructors with solid combat experience. They are trained as members of assault forces, snipers, aerial reconnaissance operators, and artillerymen. Tactical medicine is also emphasized.

“We take time exclusively for exercises,” says Shevtsov, “because, as we know from experience, 90% of military officers die not from wounding but as a result of delayed medical assistance. For members of the assault troops, there are several training areas: storming trenches, urban warfare, mine clearing, working in pairs and groups, and ground movement. The instructors who came to us from the combat zone know what a soldier needs to save their life, and they share their experience.”

A lighthouse keeper in the epicenter of historic events

The warriors set up perimeter defenses, make buddy runs, storm trenches, crawl through tall grass, pull out the wounded, deploy drones, and so on. They are much more enthusiastic about the fights, even if they are just exercises, than about the interviews since they tend to get shy in front of the camera.

Oleh Fedorovych is one of those who was much more excited about the news of the sinking of the Russian flagship Moskva than others. For him, this story was something personal. Now the head of a border guard unit, he used to work as a lighthouse keeper on Zmiinyi (Snake) Island.

“The Russian flagship Moskva approached the island around five in the morning,” he recalls the beginning of the full-scale invasion, ”and it began to intimidate and threaten our border guards, offering them to defect to their side. As I watched the border guards act, I decided that I only wanted to serve in the State Border Guard Service. Because in one moment, everything changed, and I saw how bravely our border guards behaved.”

He witnessed the historic ‘bugging off’ of the Russian warship and watched as the brave men were captured. He was one of the two civilians on the island, and the Russians allowed them to leave.

“A month later, I came to the recruitment office and asked to join the border guard,” Oleh Fedorovych says. “So now I’m here. I have no combat experience. The 17th Border Guard Unit was stationed in Izmail. We protected the state border. Later I volunteered for the Steel Guard to test myself. I attended a course for squad commanders at the training center and am now learning fire tactics and tactical engineering. As a squad commander, I must communicate with people and build good relationships with them.”

Currently, Zmiinyi Island is under Ukrainian control, but the lighthouse was destroyed. It even survived World War II, but not the Russian invasion, notes the border guard. “We will rebuild it,” he adds.

The Ghosts and a former assistant judge

Stanislav joined the army shortly after the full-scale invasion began. Earlier, he worked as a lawyer and assistant judge. Just about to retire, he also had a business making playgrounds for children. Stanislav admits that he set aside his family’s concerns after seeing the atrocities committed by the occupiers. Preserving sovereignty—”how we live and what we will leave to our children” – came to the fore.

He first fought in Bucha as a member of the Territorial Defense Forces, and in July, he joined the 94th Border Guard Unit.

“I fought in the combat zone near Vuhledar and Bakhmut,” he says. “After the rotation, I returned to the military base and saw the recruitment ad for the Steel Guard. I was one of the first members of the 94th unit to apply for a transfer to the 15th Mobile Unit.”

He says that each member of his unit has their own area of responsibility and is a professional in their field. Like everyone else, he underwent additional training to improve his skills.

“I’ve been trained in almost all the skills we need to make sure our children can go to kindergarten safely. Now I try to pass those skills on to others,” Stanislav says.

He also stresses the importance of premedical care and says that misapplying a tourniquet is one of the most common mistakes made by beginners.

“Then there’s the problem of interaction when everyone knows everyone else, but there’s no interaction,” he says, listing the stumbling blocks they have faced. “We eliminate that from the beginning—to the point that we put people in groups of two. You could jokingly say it’s a couple that always goes together. There are twos, threes, and fours. People know everything about each other, and that way, you already get a ready-made squad that can do tasks.”

A young man with the call sign “Awl” hides his face before the interview begins. He is one of those who chose military service as a profession. After finishing ninth grade, he enrolled in the military lyceum and then in 2018 at the National Academy.

“The all-out war started on February 24, and on March 3, we had an early graduation ceremony,” he recalls. “I was sent to the Kharkiv border guard unit and took part in the defense of Kharkiv until September 10, when we reached the state border.”

He and his fellow soldiers ‘felt the taste’ of war as soon as they arrived—they immediately came under rocket fire.

“It was chaos. No one knew what was going on,” Awl recalls. “The occupation forces were stationed just outside the town of Derhachiv and the village of Lisne on the M-20 ring road around Kharkiv. That’s where the first battle took place. It was brief, but I remember it all too well.”

He later fought in the legendary guerilla unit, The Ghosts of the Gray Zone, and now serves as the platoon’s deputy commander.

“After we reached the state border in the Kharkiv region, we stopped moving and only maintained the defense,” he says, explaining his decision to join the Steel Guard. “I wanted to get new emotions, so I applied for transfer to the Steel Guard’s assault brigade.”

During drills, he helps medical and combat training instructors and learns a lot of new things from other instructors as well.

From an airport near Kyiv to the outskirts of the Donetsk Airport

Vladyslav used to work at the airport of Boryspil. His civilian life was over on February 24, 2022, along with his job, when the airspace of Ukraine was closed. On February 27, he and his older brother went to the recruitment office to sign up as volunteer fighters. Their first task was to defend the Boryspil airport, which was attacked several times. Later they served in the 24th Border Guard Unit, which guarded the border with Belarus, and in June, they were transferred to the Donetsk combat zone. This was the most brutal war experience for Vladyslav:

“We were in Heorhiyivka for a month and then went to Avdiyivka near Pisky for two months. The first days were scorching hot, and there was so much fighting, just hellish. We fought back fiercely, there was artillery fire, very heavy, and their tanks worked well, very well. And then I suffered shell shock, spent a month in the hospital, and then returned to my comrades.”

His most painful memory is also associated with this battlefield. He came to the position to take over and learned that his comrades there had been killed. They had been friends for seven months.

Vladyslav was transferred to the Steel Guard along with his brother. He serves as a combat medic and assistant anti-tank grenadier.

As part of his training, he visited the UK to learn and improve his first aid skills.

A mountain landscape is tattooed on his arm. He says the two peaks symbolize his two dreams: to try skydiving and travel abroad.

“One of them came true when I went to the UK, so now only skydiving is left,” he says cheerfully.

Students defending their country instead of their theses

Ivan joined this unit straight from the classroom, having just graduated from the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute with a degree in chemical engineering and technology. He is serving in the army and, at the same time, pursuing his master’s degree through distance learning.

“I’ve been serving in this unit since February when it was formed,” he says. “I’m the gunner of light anti-tank weapons like NLAW, Javelin, Fagot, and Metis. We were trained in a specific area and now have drills in general tactics, firearms, and tactical medicine. We participate in the daily routine of the unit, so to speak.”

Ivan is from Nizhyn, a town in the Chernihiv region, and between his studies and military service, he found time to volunteer and help members of the Territorial Defense Forces at checkpoints.

“It’s funny that when I was in tenth grade, the recruitment office declared me fit to serve in the State Border Guard Service,” Ivan says. “I was curious about it, and now I could choose the post and the unit I wanted to be trained in. So I joined the Steel Guard. Why anti-tank weapons? I think they decided that based on my abilities because I worked with a level on a side job during the summer. And then my athletic build. I can haul anti-tank weapons easily. And they’re pretty heavy.”

Ivan is tall and stocky and is called Po by his comrades, like the protagonist of Kung Fu Panda.

His parents, sister, friends, and university professors are waiting for him to return from the war. He admits that it is impossible to fully prepare for war, but if the order were given now, he would overcome the anxiety and go to the front line at that very moment.

We record the interview with our youngest hero to the hum of a drone. “Afonia” is only nineteen. He is a student and joined the unit when he was eighteen. By law, only people over 25 can be drafted, so Afonia visited a few recruitment offices and did not enlist until the third attempt.

“They rejected me and told me I was too young and should sit at home and study,” he says. “But I think that’s my duty. All the guys here think that, too. I’m not the only one that young.”

Afonia studies telecommunications and radio equipment. Here he is responsible for countering unmanned aircraft and also works as a drone operator. He believes that drones effectively support reconnaissance, as all information can be provided to the infantry at a distance of a few kilometers.

At his young age, he already has experience working in a software development company. His call sign stuck with him back at his civilian job.

“We were trained to fly drones, many different types, and also to shoot them down and jam them so the enemy could not sneak up on us,” Ivan says, listing the skills he had to master. “We also learned to shoot and run with all kinds of weapons. There was physical training, shooting drills, and camo and concealment course. Learning to pilot a drone was the most difficult because you can’t do it right from the get-go. You have to learn to maneuver and transmit information and coordinates.”

A chevron with Alien’s silhouette on his bulletproof vest is a gift from his brother, who serves on the police force.

“He also took part in the combat operations during the de-occupation of Kharkiv,” he says proudly. “My father also fights, so I sort of followed in their footsteps.”

After completing their “mission,” the young men take off their bulletproof vests and helmets, greedily gulp down water, smoke, and line up with their bowls to get porridge with canned meat. In a hypothetical tomorrow, they will face battles and tasks that will have nothing to do with exercises. Not only the life of each of them but, without exaggeration, the existence of Ukraine as a sovereign state will depend on their success. But for the moment, they enjoy a brief rest and lunch in the shade of a summer forest.

“Today, all of us, all security agencies—the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the State Border Guard Service—are performing an important task,” says Ivan Shevtsov. “We are defending our country. We all have one and the same mission: to liberate our territories and reach the 1991 borders. All who have enlisted, all military officers are working for a single cause. During combat operations, the State Border Guard Service switches to combat mode and operates on equal footing with other units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. And our task is to train the fighters and launch the counteroffensive soon and liberate the occupied territories.”

Before we say goodbye, we joke that we will film the next reportage about the same guys in the village or town they liberate. We really hope that this will happen. And that the lighthouse on Zmiinyi Island will serve as a beacon again.

Text: Olena Maksymenko

Photo: Danylo Dubchak, Yeva Fomycheva, Olena Maksymenko

English translation: Hanna Leliv

Матеріал створено в рамках проєкту «Життя війни» за підтримки Лабораторії журналістики суспільного інтересу та Інституту гуманітарних наук (Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen)